THE OBELISK OF MANISHUTSHU IN CONTEXT

Manishtushu Standing Statue from Susa.pdf

Manishtushu Standing Statue from Susa.pdf  Chart of the Fields of the Manishtushu Obelisk.pdf Map Showing the Four Main Cities of the Manishtushu Obelisk.pdf

Chart of the Fields of the Manishtushu Obelisk.pdf Map Showing the Four Main Cities of the Manishtushu Obelisk.pdf

Manishtushu’s Reign

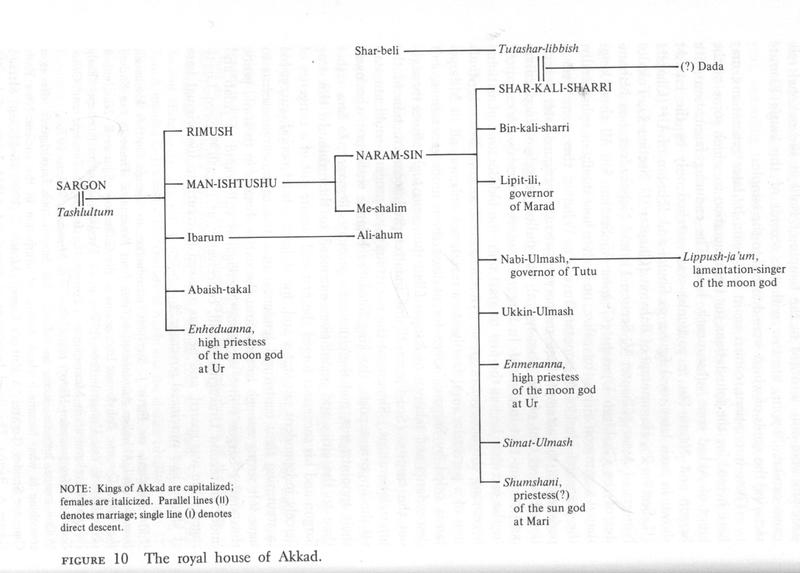

The degree to which Manishtushu’s reign (or the reigns of any of the Sargonic rulers) can be reconstructed is regrettably modest. Not only is there a dearth of evidence stemming from his own time, but there are also notable biases in subsequent accounts of his reign.[1] Even his order within the dynasty is disputable, but scholars tend to situate him as the third ruler after Sargon and Rimush. Furthermore, he typically regarded as the elder brother of his predecessor Rimush and son of Sargon. His ascendency and later death are also shrouded in mystery, but it has been conjectured that he played a role in the conspiracy to assassinate Rimush and that he himself was later assassinated.[2]

Though these details and many more cannot be ascertained, some highlights from his reign can be fleshed out. First, upon ascending the throne, Manishtushu inherited a still nascent empire with many challenges that required military action. His military campaigns probably took him in several directions, one of which being against Elam and across the gulf to Makkan. This campaign, which is described in his “Standard Inscription,”[3] resulted in the acquisition of valuable diorite stone (among other luxuries), that he would use for various monumental works. Second, Manishtushu proliferated monumental works, mainly in the form of dedicatory statues of himself, which he had placed in various temples across his empire. Though these monumental works were directly focused at various deities and had theological motivations, they certainly functioned politically to bolster support for his rule among various peoples.[4] Third, Manishtushu oversaw the purchase of eight parcels of land, which he reorganized for distribution to secure loyal dependents, which was commemorated and validated by his obelisk.[5]

The Obelisk

Description

The Obelisk of Manishtushu is an impressive monumental work to say the least. It is a diorite stele, pyramidal in form (though with uneven widths), which reaches a maximum height of 144 cm. (including a 10–20 cm. plaster base). Now housed at the Louvre, it was excavated from Susa in Elam (where it was brought after the sacking of Babylonia by Shutruk-Nakhunte in the 12th century) around the turn of the 20th century, but the location of its original deposition is disputed.[6] The stele is inscribed with lapidary Akkadian writing on all four sides with a total of 1,519 registers.[7] Besides being lapidary in nature, the writing is notably excellent in quality and can be considered imperial by virtue of its carefully executed and standardized script similar to other monumental works from its time.[8]

Genre, Structure, and Text

This inscription belongs to a genre of inscriptions generally classified as ancient kudurrus (applied anachronistically because of their similarities to Kassite kudurrus), concerning which Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., write:

ancient kudurrus deal with the acquisition of landed property by a single buyer from several sellers, the latter often being related to each other by blood. Thus, ancient kudurrus testify to the existence of a land tenure system based on family-owned property, contradicting the reconstructions of all those scholars who visualize land ownership as being limited to the state or the temple.[9]

The text is structured according to its presentation on the stele, with each face of the inscription detailing a separate transaction:[10]

|

Face |

Column and Line Breakdown |

Content |

|

A |

i |

Introductory Statement |

|

ii 1–v 16 |

Transaction A1 |

|

|

v 17–viii 4 |

Transaction A2 |

|

|

viii 5–ix 8 |

Transaction A3 |

|

|

ix 9–xvi 23 |

Details Concerning Transactions A1, A2, and A3 |

|

|

B |

i–xxii |

Transaction B |

|

C |

i 1–vii 17 |

Transaction C1 |

|

vii 18–xii 5 |

Transaction C2 |

|

|

xii 6–xiii 9 |

Transaction C3 |

|

|

xiii 10–xxiv 29 |

Details Concerning Transactions C1, C2, and C3 |

|

|

D |

i–xiv |

Transaction D |

Concerning the content of the text, Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., note:

The inscription deals with the acquisition of eight parcels of land, each from several sellers of the same kinship grouping, by the king Manishtushu. These eight parcels, totaling 9723 (= 3430 ha) of land, are situated in four areas around the cities Dûr-Sin, Girtab, Marda, and Kish, all in the land of Akkad.[11]

Overall, the text is minutely detailed,[12] noting that Manishtushu, “king of the totality,”[13] purchased the land for 31/3 shekels of silver per iku of land. Moreover, the text indicates that all of the sellers were Akkadian, with one Sumerian exception.

Interpretation

Though the kudurru describes a land purchase, noting that all of the sellers were paid, the sale was likely compulsory and the sellers were probably under duress, as Foster describes:

About 2260 BCE, 964 men in the land of Akkad sat down to a royal feast, but they had little to celebrate. True, some had been given new clothes and jewelry. Some boasted new teams of mules and a wagon to go with them, as well as implements and other gifts. A few had sufficient cash to buy and furnish good-sized houses. The food, no doubt, was excellent, probably pork roasted over an open fire and assorted delicacies more typical of the royal table than of private life. Yet these men had just sold their ancestral lands to the king, Manishtusu, son of Sargon. Since portions of these lands bordered on royal domains, their owners could scarcely have refused the king’s offer. Using a productivity ratio from irrigated lands farther south, we find that the price paid in grain was only two years’ estimated harvest. What farmer would willingly sell his land for that amount?[14]

After the land was purchased and taken from the landed gentry, it was given to forty-nine Akkadians who were probably officials, both civil and military, who were loyal dependents of Manishtushu. These officials were probably part of a newly-formed elite that were willing to be redistributed to assume ownership of these parcels of land.[15] Thus, this purchase is more of a confiscation or expropriation of the land than a commercial endeavor and its purpose was to centralize power by reorganizing land ownership, which, in turn, also affected local leadership. While the arrangements could have theoretically been managed without the production of such an elaborate kudurru, the writing of this deal on stone both commemorated and validated this action. As an enduring monument, it would have served as a reminder to both the literate minority and (through heralds and word of mouth) the illiterate majority of the deal the king arranged.[16] Not only did this kudurru commemorate the purchase, but it validated it by laying out in detail all of the parties involved and the “fair” price that was offered as in other ancient kudurrus.

[1] Such accounts include the “Sumerian King List,” the “Curse of Akkad,” and Manishtushu’s “Cruciform” inscription (which is a later forgery, much like the “Donation of Constantine”), as well as other inscriptions, including omen texts. See J. J. Finkelstein, “Mesopotamian Historiography,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107 (1963): 461–72, and Finkelstein, “Early Mesopotamia, 2500–1000 B.C,” in The Symbolic Instrument in Early Times, vol. 1 of Propaganda and Communication in World History, ed. Harold D. Lasswell, Daniel Lerner, and Hans Speier (Honolulu: East-West Center, 1979) 50–110, especially pp. 59–83.

[2] See Piotr Steinkeller, “Man-ištūšu: Philologisch,” RlA 7:334–35.

[3] See Douglas R. Frayne, Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC), RIME 2 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 74–77.

[4] See Melissa Eppihimer, “Assembling King and State: The Statues of Manishtushu and the Consolidation of Akkadian Kingship,” AJA 114 (2010): 365–80. She writes;

Of course, the effectiveness of this program depended on the target audiences’ ability to perceive the standardization and replication of the royal image as a sign of Manishtushu’s simultaneous and equal attention to the gods of each city that was now incorporated into the Akkadian state. Among human viewers, those capable of recognizing any one statue as belonging to a larger, uniform set could have included, at the level of production, the scribes responsible for the inscriptions and the artists who created the statues. At the level of consumption, the audience is more difficult to identify, but it would have included those who had the means, the need, or the right to travel from city to city and temple to temple. Beyond the human audience, Manishtushu’s message could have been directed to the gods themselves, whose visits to other gods in their temples were an essential part of Mesopotamian religion. Through this mobility, the gods could have observed the ruler, in his various sculptural manifestations, as a permanent and equal presence in the temples. (378)

[5] See Ignace J. Gelb, Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert M. Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus, The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 104 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

[6] Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 116, note that it was probably taken by Shutruk-Nakhunte from Ebabbar, the temple of Shamash at Sippar, but Aage Westenholz, “The Old Akkadian Period: History and Culture,” in Mesopotamien: Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit, OBO 160, ed. Pascal Attinger and Markus Wäfler (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999) 15–117, p. 44, n. 138, writes that it was probably deposited at Akkade.

[7] See Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 116, for a further breakdown of the column and line numbers per face of the stele.

[8] See Mario Liverani, The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy, trans. Soraia Tabatabai (New York: Routledge, 2014), 141.

[9] Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 2.

[10] See Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 116.

[11] Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 116.

[12] It describes in incredible detail the price paid, the names and relations of all of the sellers and witnesses, and the locations of the parcels of land being sold. For further information, see Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 116–40. For an analysis of the sellers and their relationships to one another, see I. J. Gelb, “Household and Family in Early Mesopotamia,” in State and Temple Economy in the Ancient Near East, OLA 5, ed. Edward Lipiński (Leuven: Department Oriëntalistiek, 1979), 1:1–97, especially pp. 73–88.

[13] A I 6–7, which reads LUGAL KIŠ, according to Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting, Jr., Earliest Land Tenure Systems, 119.

[14] Benjamin R. Foster, The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia (New York, NY: Routledge, 2015), 1.

[15] See Foster, Age of Agade, 1.

[16] For the dissemination of information through public monuments to both the literate and illiterate, see Finkelstein, Early Mesopotamia,” 50–54. Note that he is reluctant to describe early monumental works as propaganda, though they did serve political ends. See Westenholz, “Old Akkadian Period,” 26–28, for a similar argument.